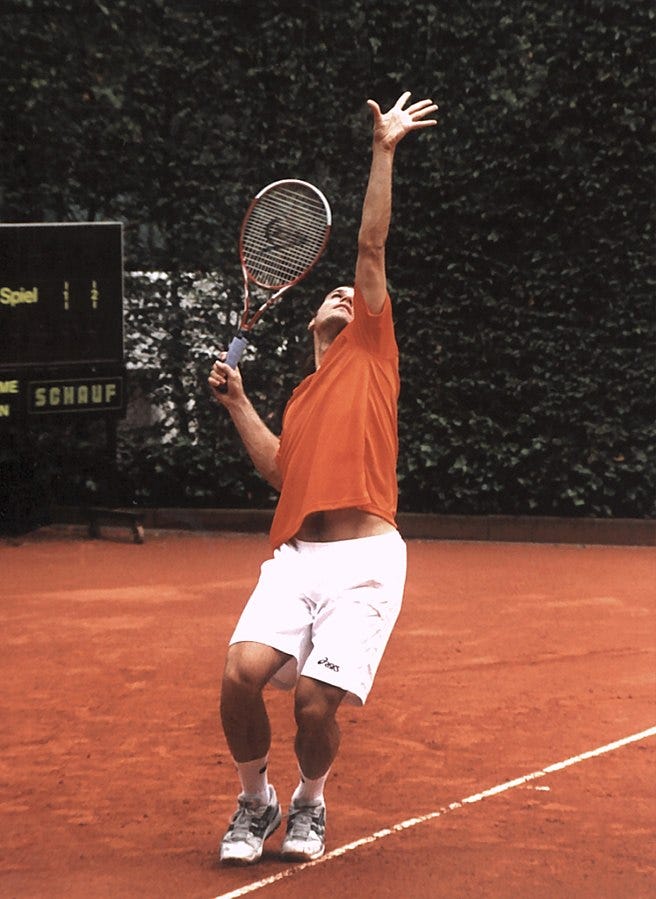

Change is Hard, But This is the Way. See. Do. Teach. SeeI took tennis lessons once. The coach asked me to show him my serve. I hit a few. I looked over and saw him shake his head. "We have a lot of work to do," he said. First, he had me put my racquet down and practice tossing the ball up in the air. He showed me what I was doing wrong. I was bending my elbow, causing the ball to go behind me where I couldn't hit it well. He showed me how to toss it right. "Keep that elbow straight," he said. This simple interaction reveals the first crucial step in any change process: accurately identifying what's not working and learning a better alternative. In both tennis and life, we often struggle not because we lack effort, but because we haven't seen the problem or the solution. First, you must know what sanity is and compare it to what you've been doing. You have to know how to do it right to know what you're doing wrong. Psychotherapy involves learning to do things differently. The couple who's coming in for marriage counseling needs to learn to listen and respond differently. The anxious person must learn to relax; the depressed one, how to keep going; and the addicted one, why and how to stop using their substance. Every person must be able to observe themselves accurately and compassionately, and then to do something new. Imagine an alcoholic. She's gone to AA and gotten a list of phone numbers of recovering people they can call whenever they feel like drinking. These people will talk her out of it. What she's got to do is to call them when she has what passes for a reason to drink. It's a very simple operation, as simple as tossing a tennis ball while keeping your arm straight. By the way, my tennis coach went on to show me other things I could use to improve my game, but what really stuck with me was how to perfect the toss. That was the only thing I learned from those tennis lessons. It turns out, that's all I needed to learn so that I could beat the people I was likely to play. Sometimes, mastering just one fundamental element is enough to transform your entire game, or your entire life. Similarly, every therapeutic journey begins with this recognition: seeing the problem clearly and learning a specific, actionable solution. Do, Over and Over, AgainMy tennis coach watched me toss the ball until I did it correctly. Then he had me hit it after I tossed it that way. I hit a perfect serve. "There," he said. "Now toss it that way two thousand times in a row and it'll be automatic." My coach understood how to effect change. First, he had to break down the process of serving a tennis ball into parts small enough for me to see. Just the toss. Then, he knew that to break old bad habits and create new ones it is necessary to repeat the new habit over and over again. How many times? I don't know if two thousand times is the precise number necessary. Suffice it to say, it's a lot. Let's go back to the alcoholic. If she's called her friends at AA once, she's achieved a small victory. If she's called them two-thousand times, she's changed a bad habit into a good one. It may now be automatic. It might take me an hour to toss a tennis ball correctly two-thousand times, thus creating a good habit quite easily. It's not so easy when she trains herself to call her AA friends. She would have to have two-thousand urges to drink and two-thousand phone calls. That would take years. This is one reason why so many people relapse, so many people say change is impossible, and so many people give up. But change is possible. It just takes persistence. Very small changes, if they're the right changes, can make a huge difference. But you've got to practice. This is where drilling comes in, otherwise known as repeated conscious practice. No one likes to drill, but a musician who hasn't done his scales will not know how to play. An actor who hasn't rehearsed does not know her lines. A basketball player who hasn't shot from the foul line countless times will not score a point when the game is at stake. The idea of drilling is to repeat something often enough so you can do it in your sleep. Learning a new emotional or behavioral skill is harder when you need to use it when you are under extreme duress. It's one thing to learn to listen, how to calm yourself, and how to stop using drugs. It's harder to listen when your spouse is yelling at you, how to calm yourself when you think you're going to die, how to go on when you wish you would die, and why and how to stop using a substance when it seems like nothing but the substance could solve your problem. You need to be able to observe yourself accurately and compassionately when you are the most ashamed. That's hard. It's as hard as a surgeon learning a new procedure, not on a patient, but on himself, blindfolded, without anesthesia. To be able to learn to do that is going to take more than doing it two thousand times. It's going to take ten thousand. If you've got serious problems, you can't just go to a shrink's office, unload them all, and walk away a new man. You'll be disappointed. You might feel better for a minute, but if you go home and do the same things you've always done, you'll get what you've always got. If change is ever going to occur as a result of therapy, then most of the work, and the drilling, must occur between sessions. The anxious person must take up meditation; the depressed one, action; and the addicted one must repeatedly choose not to use his substance. Everyone must practice repeatedly when it's easy if they're ever going to have a chance of doing it when it's hard. However, there is one more thing you can do to accelerate the learning. Teach what you've learned to someone else. TeachA surgeon once told me they have a saying in medicine: see, do, teach. Only when you complete all three can you say you know the procedure well enough to do it on your own. Seeing means you watch someone perform a surgical procedure. When you try your hand at it under supervision, you are doing. Teaching requires you to explain it to someone else, so they can do it, too. There's a lot of wisdom in this method, which can be applied with variations to almost any kind of learning. It's not enough for me to tell you how you can calm yourself down in sixteen seconds by square breathing, you must do it. Do it two thousand times when under stress or ten thousand times if calm. If you don’t have that kind of time, then explain to someone else how to do it. I have often found that I think I know something when I start writing about it, only to be confronted by all the ins and outs of the topic before I've reached the end of the page. Teaching someone is how you work out the kinks in a skill and develop real mastery. If you really want to learn something, learn it well enough to explain it to your grandmother. This is where genuine transformation happens - when we internalize a skill so deeply that we can illuminate the path for others. By teaching, we also reinforce our own commitment to the new behavior. Just like perfecting that tennis ball toss, the path to meaningful personal change requires identifying the fundamental elements, practicing them with dedication, and teaching others; trusting that these consistent efforts will eventually transform your life. You're currently a free subscriber to The Reflective Eclectic. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Monday, 19 May 2025

What My Tennis Coach Taught Me About Change

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Franklin vs British East India Co. Slavery and Origins of Continental Congress (Colin Lowry Lecture)

On Sunday June 29, historian, lecturer Colin Lowry presented a lecture to the Rising Tide Foundation titled: “How did Anti-Slavery and the S...

-

https://advanceinstitute.com.au/2024/04/24/sunnycare-aged-care-week-10/?page_id=...

-

barbaraturneywielandpoetess posted: " life on a rooftop can be short ; depends whether one looks down or up . ...

No comments:

Post a Comment