Why do trauma victims re-experience their trauma in flashbacks and nightmares? We need some help from Freud to explain. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Freud noted that, in their dreams, flashbacks, and patterns of behavior, trauma victims compulsively repeated their horrible experiences as if they were happening in the present, rather than remembering them as events of the past. If you believe people do whatever is pleasurable, you will not expect this. Freud came up with the death drive to explain. This is how the death drive works. Death awaits you. Not just death, but dissolution, nothingness, and extinction, the state of everything being totally fucked up. The Abyss. You prefer not to think about it, but it forces itself into your consciousness when you have a close call, a trauma. Your trauma gave you a glimpse of the Abyss before you have had a chance to live life fully. It brought you to the brink and threatened to push you off. You would like to be prepared next time, so you don’t fall in before you’re ready. Having a death drive doesn’t mean that you want to die. Far from it. You know you will fall into the Abyss, but you want to do so on your terms. You attempt to master the inevitable by compulsively repeating the event that brought it to your awareness. When you have a close call with the Abyss, you’ll go over it again and again and again. This compulsion to repeat the trauma is to keep up the vigilance which you think you failed to have in the past. You can’t take your eyes off the Abyss, no matter how much you’d like, because of the threat it poses. You want to be prepared next time. Flashbacks are rehearsals. Here’s where I’d go further than Freud did with the death drive. The moment you have any desire, you seek to extinguish the desire. When you crave chocolate, you mentally rehearse the eating of chocolate in the same way that trauma victims rehearse teetering at the edge of the Abyss. All desire naturally heads towards fulfillment, and all life heads towards death. It’s just like when you read a novel. The hero in the story has a desire. The boy desires the girl; the detective desires to solve the crime; the vampire desires blood. If the book hooks you, you soon have a desire, too: to keep reading until the book is done. A good ending achieves a sense of resolution when all desires are settled, and all the loose ends tied up. Unfortunately, the book, then is done and you can’t read it with the same anticipation anymore. But there’s more, and so novels are long: not too long, not too short, but of a certain length. When you crave chocolate, you know it’s not that enjoyable to just cram it into your mouth at once. The craving can be enjoyable, too. If you look forward to the chocolate, delay your gratification; if you lick it, savor it before consuming it, then you enjoy it more. This process is what Freud calls binding. The more you tease yourself with the desire, the more you rehearse its satisfaction, the more you tightly bind yourself to it. Besides its original importance, the desire, once it’s bound, becomes invested with all the energies generated by delay. When you read, you want the hero to be successful, but only after having adventures, suffering setbacks, and acquiring helpers. First, there’s the hero’s desire that drives the plot forward. Then, there’s the delay, the detour, the arabesque, the refusal of closure, the making of bad choices. This fills the pages in the middles of literary plots. Subplots, with their own system of desires, setbacks, and resolutions, contribute to the delay. A satisfying story, by teasing you with the ending, binds these elements together. In a good book, everything is there for a reason. In summary, in real life, just as in fiction, whether there has been trauma in it, or not; life moves toward death. You know you’re heading for the Abyss, but you want to do so on your own terms, after having had a full life. A full life comprises the same desires, setbacks, adventures, and delay we find in fiction. It is enriched by the subplots provided by your associates. An awareness of the end adds a great deal to the story by bringing to mind what’s at stake. Trauma adds drama. The pleasure principle and the death drive coexist and cooperate in the developing and enriching of a good life, as it does in the developing and enriching of a good plot. You're currently a free subscriber to The Reflective Eclectic. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Monday, 5 May 2025

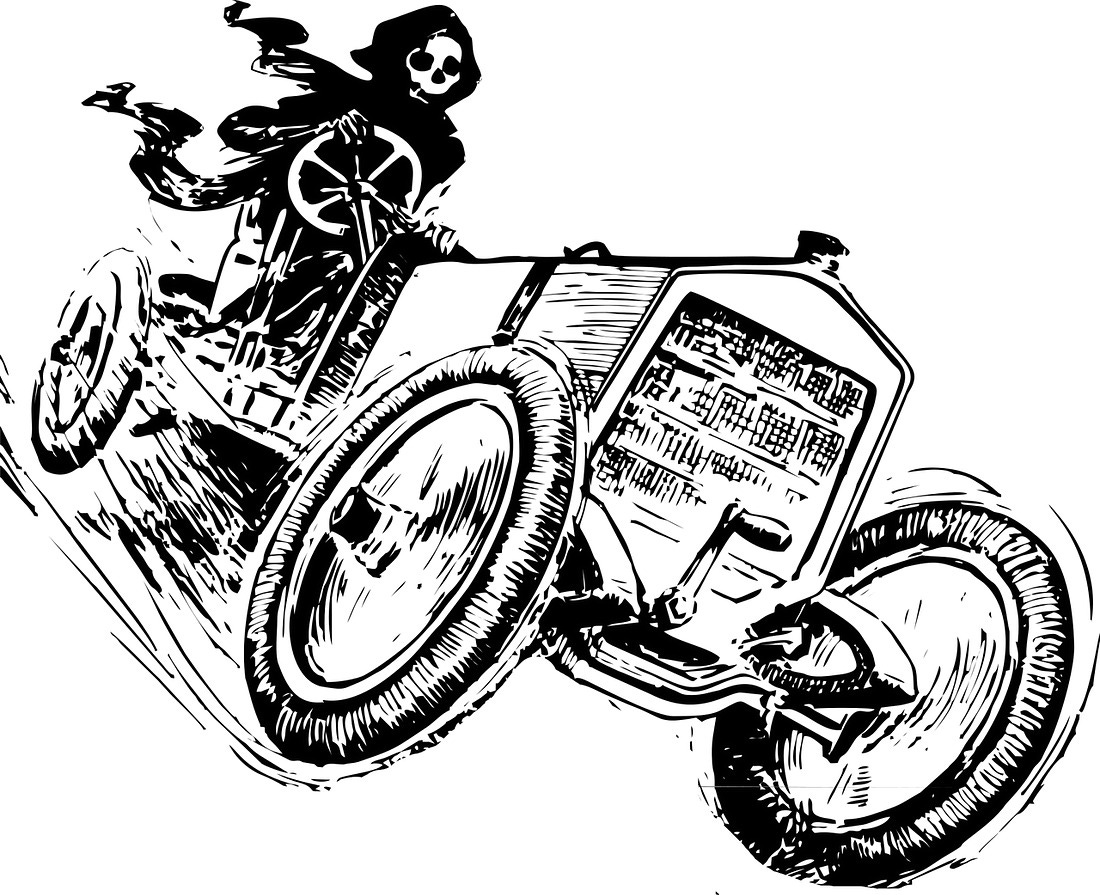

Driving to Death

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Sunday Event #2: Trotsky and the Neoconservatives: Lets Talk About the Trajectory of Liberalism at 2pm ET

Speaker: Caleb Maupin ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

Welcome back to America's #1 Daily Podcast, featuring America's #1 Real...

No comments:

Post a Comment