There’s colonization going on everywhere, between family members as well as between nations. The classic way of being colonized is when you come from a poor country that’s dominated and exploited by a richer one. The key giveaway is an internalized sense of inferiority. But I believe everything we know about the psychological effects of colonization can apply to any relationship when there is an imbalance of power. Sometimes you’re both the colonizer of those who have less power and the colonized of those who have more. Colonization, in this expanded sense, is whenever someone with more power gets inside your head and starts calling the shots. It's not just about taking over land or resources, it's messing with how you see yourself and the world. This can happen in all sorts of relationships, from bosses and workers to parents and kids, or even just society pushing you around. It usually sneaks up on you. Before you know it, you're thinking the way The Man wants you to think, doubting yourself, and maybe even defending the system that's keeping you down. It's like they've set up shop in your brain, making you believe their way is the right way. The end game? Keeping the power balance tipped in their favor by getting you to play along, often without even realizing you're doing it. Frantz Fanon

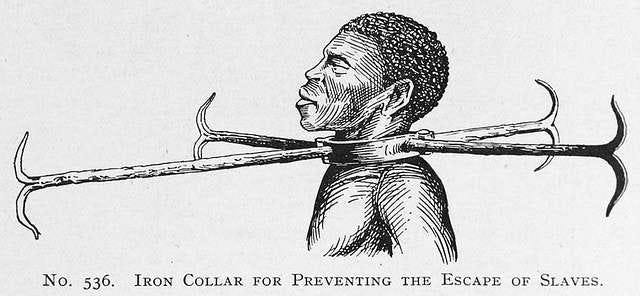

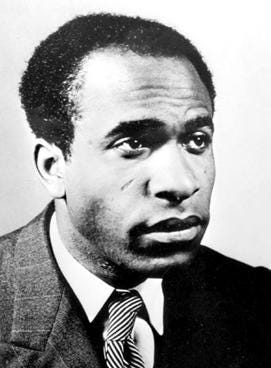

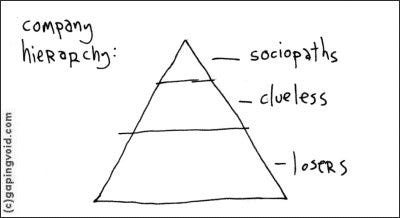

If you want to know anything about colonialism, you must start with Frantz Fanon, who may be one of the most influential therapists of all time. Despite few people hearing of him, he’s right up there with Freud, Piaget, Skinner, Maslow, and Pavlov and his dog; way past John Bradshaw, Dr Phil, and Jordan Peterson. If you don’t know who he is, you can blame colonialism, which aims to keep folks like him silenced. Fanon was a psychiatrist, born in Martinique in 1925 when it was a French colony. He ran a psychiatric hospital in Algeria, another French colony, and got involved in their war for independence. He wrote two books that expose the psychological effects of colonialism on the colonized: Black Skin, White Masks, and The Wretched of the Earth. He’s been quoted worshipfully by revolutionary groups as varied as the Black Panthers, the South African Black Consciousness movement, Latin American guerrillas, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and the Islamic revolutionaries of Iran. Many claim he advocated terrorism. How does a therapist become a revolutionary, and a bloodthirsty one, at that? It starts when he believes his patient’s mental health problems are more than a neurological disorder of the brain; they’re shaped by social relationships. His patients are crazy because the world is crazy. Healing them involves healing the whole world. As a Black man in the French empire, Fanon had personal knowledge of how crazy-making colonialism can be. Colonialism is based on racist or classist conceptions of the colonized and their inability to take care of themselves. These beliefs are backed up by political and military power and justified by doctors and scientists who pervert the scientific method to demonstrate why the colonized are inferior and need to be colonized. When European colonists first took over the island that we call Martinique, they enslaved the native people. When they died off, the colonists imported slaves from Africa to replace them. As time went on, the Martiniquais built a society that not only maintained the basic division between Black slaves and White masters, but differentiated field slaves from house slaves and overseers, and used the house slaves and overseers to protect the masters from the field slaves. In a colonial society, only the culture of the colonizer has value; the culture of the colonized is said to be primitive or childish. The colonizer’s language, history, law, religion, medicine, and technology are considered better in all respects and become the only things taught in schools. Those of the colonized are pushed to the margins. Some, who have adopted the culture of the colonizer, are given slightly more status over the field slaves. They attempt to mimic the culture of their masters by speaking like them, thinking like them, and behaving like them. They value their master’s culture over their own. They become the house slaves and overseers, but they are never given full acceptance. The greater part of a colonial society is formed from the field slaves. These are the folks who get the least from being colonized, but also give the least. They do the minimum required of them. They adopt some of the master’s culture, but not as much as the house slaves and overseers. They may not talk, think, or behave like the master, but generally believe the master when he says that they are primitive, childish, and in need of someone to tell them what to do. There is a fourth part to a slave society that’s often not mentioned because it has mostly left the social order. These are the Maroons, or escaped slaves that form separate societies of their own like the Great Dismal Swamp Maroons of Virginia and North Carolina and the Palmares of Brazil. Others link with neighboring cultures like slaves of the southern United States who joined with Native Americans to create the Seminoles or West Indian slaves who joined disaffected Whites to become the pirates of the Caribbean. These are all people who chose to step out of colonial empires and make it on their own. They represent a threat to the colonial masters, who go to war with them when they can find them and fight ideological battles when they can’t. If you don’t know much about Maroon societies, you can blame colonialism, which not only seeks to suppress them, it all but erases them from consciousness. The structure of a slave society persists even after outright slavery is abolished. The Martiniquais where Fanon was born hadn’t had slavery in hundreds of years, but it still had that same structure. It’s the structure of any colonial society. House slaves became the professional class, field slaves became the working class, and the masters returned to France, but kept their influence. Fanon was born in the professional class. He had whiter skin than most Martiniquais, which was a sign of that class’ slightly elevated status. He spoke excellent French and was indoctrinated into French history and culture. He fought valiantly for the French in World War II and became a physician after the war. Then he immigrated to France and rose to a position of prominence in his profession. He palled around with two of the most famous French people of his age, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. Fanon was as successful as a Black person could be, but he was never accepted as a Frenchman. Casual encounters with Whites in France taught him he was different. He was Black to them, even though he was not Black to himself. Disguised ColonialismYou don’t have to live in a colonial society to be colonized. According to Venkatesh Rao in his book, The Gervais Principle, modern corporations take a form we can recognize as colonial. At the top of most corporations are executives who extract a greater share than everyone else in the corporation. They’re like the colonial masters; Rao calls them the Sociopaths. At the bottom are ordinary workers who are given as little as possible. They are similar to the field slaves who have no choice but to accept a bad bargain but have no illusions that they’ll ever get anything different. Rao calls them the Losers. The whole arrangement hinges on the middle managers, the Clueless to Rao, who correspond to the house slaves and overseers of a slave society. They’ve been told they can get ahead by playing the game and busting their butts for the company. The Sociopaths/colonial masters snicker, give the Clueless/house slaves a little more than the Losers/field slaves, and use them as shields from the Losers/field slaves. The Clueless/house slaves believe they’ll rise in the organization; but they never will. They don’t understand how the game is played. It’s played according to the rules set by the Sociopaths/colonial masters, not the rules in the employee handbook. You have other choices besides joining the rat race. In some ways, it’s better to be a Loser/field slave. Just go in, punch the clock, do the minimum, and derive most of your satisfaction outside of work. Or you can be like an escaped slave and form something like a Maroon society that used to exist on the fringes of colonial empires. In various points of my life, I’ve occupied every class. I started off as a Maroon when I was a hippie homesteader, in an attempt to avoid said rat race. Then I got sucked into the Loser class, stuck in dead end jobs that weren’t going anywhere. Eventually, I was promoted to the ranks of the Clueless, until I caught on to the game. That’s when I quit to go my own way, to private practice; only to become a Loser again, working the fields of the insurance companies. Now I’m back to being something of a Maroon, not beholden to any master. If I was a more influential writer, I’d be a Sociopath. The most effective Raoian Sociopath doesn’t hold a whip, he’s a writer. How the Colonial Master Masters Your MindWe should not take Rao’s typology seriously. He seems to have chosen his terms Sociopath, Loser, and Clueless for their shock value, not their accuracy. Rao’s Sociopaths aren’t necessarily evil. They’re the meaning makers and, as such, they create their own rules. They construct entire systems of thought to guide and direct the flow of credit and blame to their advantage. No one in the colonial system objects. Rao’s Clueless and Losers are grateful to the Sociopaths for taking the burden of defining reality off their shoulders. The Clueless crave rules, clear rewards, and certain punishment. The Losers just want to belong to something greater than themselves. The Sociopaths give it to them. It can be hard to understand just how the Sociopaths hoodwink everyone else if you’re hoodwinked by them. At one time, nearly everyone thought slavery was good, even necessary. It was said that slaves would not be able to take care of themselves without their masters. It’s difficult for us to imagine thinking like this now. The only way I can do it is to imagine what people’s point of view might be of us two hundred years from now. What things do we believe that they will say is crazy? Here’s one. Capitalism is predicated on constant growth. We expect our stocks and the value of our property to be always on the rise. It can’t go on forever. Not only does the planet have limits, but the social costs of growth are numerous and overlooked. The ideology of growth mainly benefits those at the top of the economic ladder. Big corporations and their wealthy shareholders gain the most as their profits and assets grow faster than the overall economy. Political leaders use economic growth to claim success and stay in power. While some workers might see more job opportunities in growing sectors, the biggest rewards of growth usually go to those who already have money and power. This system tends to make the rich richer while the costs, like environmental damage and social disruption, are shouldered by ordinary people and future generations. How do the Sociopaths get us to believe in their self-serving ideology? Repeat a lie often enough and people believe it. A period of economic expansion leads people to believe growth is normal. It’s reinforced by governments and businesses who found it convenient to measure progress solely in terms of growth. The media pushes the idea that more is better, linking consumption to happiness. Our education systems teach economics with growth as an unquestioned good. Politicians promise growth to win votes. Over time, this growth mindset has become so ingrained in our culture and institutions that many people find it hard to imagine alternatives, even as the negative consequences become more apparent. Anyone who thinks differently is alienated. AlienationThe most effective tool the Sociopaths/colonial masters have to shape their ideology is alienation: the threat of rejection, coupled with the promise of belonging. First they defined the slaves as alien. Everything about the slaves and their culture was called primitive, childish, or simple at best; savage, heathen, and accursed, at worst. Then they alienated the slaves from each other. They set some up as the Clueless/house slaves and overseers by giving them some semblance of belonging. This class then continues the project of alienation by alienating themselves from the field slaves. That’s how Fanon grew up not thinking he was Black until he went to France and found he was alienated from the French. The whole system is pure middle school cafeteria, with everyone forming cliques, shutting out and ridiculing anyone not like them. The last step is for each colonized person to be alienated from themself. Fanon defined self-alienation as when the colonized individual internalizes the oppressor's worldview and begins to see themselves as inherently inferior. This process leads to a deep sense of disconnection from one's own culture, language, and identity, as the colonized person strives to emulate the colonizer in a futile attempt to escape their own perceived inferiority. Fanon describes this experience as wearing a "white mask" over black skin, highlighting the exhausting and ultimately impossible task of trying to become something one is not. This self-alienation not only causes personal anguish but also perpetuates colonial power structures by making the oppressed complicit in their own subjugation. If you choose to not participate in the colonial system, you can become a Maroon, the most alienated of all. The word Maroon is French for feral. It’s probably no accident that the word has also come to mean stranded on a desert island. Being left alone like that can be the most terrifying outcome. Just ask any middle school nerd, shunned by his classmates. It’s not a solution to self-alienation, either; the alienated person often hates himself the most for being alienated. Family-Style ColonialismThe social arrangements of colonialism mirror those we see in dysfunctional families. By dysfunctional, I mean a family that does not benefit all its members equally. Every dysfunctional family is centered around a big baby. When the baby is an actual baby, someone who has a legitimate call to scream bloody murder whenever they want something; there’s nothing dysfunctional about it. A true baby has no choice but to depend on other people. Sometimes, though, the baby is not an actual baby; it's a big baby, an adult who ought to be able to take care of themself or contribute in an equitable fashion to the family. Instead, they exploit the others. The big babies colonize everyone else in the family. The worst have temper tantrums until they get their way. The best make you want to give it all to them. I can give you lots of examples of big babies, the colonizers of families. It’s the patriarch that insists on total domination, the matriarch who guilts you into doing what she wants. It’s the drug addict who takes the money for groceries and shoots it up his arm. It’s the bully of the family who takes advantage; the narcissist of the family, who everyone must cater to. It’s anyone who makes everything all about them. But the most successful big baby is the kind who never needs to throw a temper tantrum. They just create a self-serving understanding of the world as they say it is, and everyone believes them. The successfully colonized family runs smoothly. Everyone knows their place. No one thinks anything should be different. But it can’t stay that way. The children get married, their spouses enter the family, see how it’s run, and say it’s crazy that things are this way. Even if the person they’re married to defends their family, the damage is done. The colonial regime is exposed. That’s when the big baby becomes most mean and controlling: when their power is threatened and they’re trying to hang on. Fanon Becomes a RebelIf you believe you’ve been colonized, what can be done about it? I mean, besides taking the Maroon option. Fanon had a lot to say about decolonization. As a psychiatrist, he worked with perhaps the most alienated of us all, the mentally ill. In fact, the mentally ill are so alienated that, not long ago they were called aliens and their doctors were called alienists. As a director of a hospital, Fanon knew that doctors alienate and colonize the mentally ill through a subtle but pervasive process of asserting power and erasing identity. They position themselves as the arbiters of sanity and use jargon and diagnostic labels to establish dominance over patients. This dismisses the patient's own understanding of their experiences, replacing personal narratives with clinical interpretations. As a doctor, Fanon found himself cast in the colonial master role. He deserves a lot of credit for not seizing the opportunity to lord it over others. Not everyone makes the same choice. Usually the colonized just become colonial masters when they can. We see this pattern everywhere, from American colonials subjugating Natives and Blacks, to Israelis oppressing Gazans. This is the way it’s passed on in families. It’s a sure method of continuing the pattern of colonization. Instead, Fanon implemented a radical approach to reverse alienation in his psychiatric hospitals. He created day programs that kept patients connected to their communities, encouraged meaningful work and social activities, and respected indigenous healing practices and languages. Fanon treated patients as whole persons, not just symptoms, and addressed societal factors like colonialism and racism in their care. He rejected the isolating tendencies of traditional Western psychiatry, instead fostering an environment that honored patients' cultural backgrounds and promoted their dignity and agency. By integrating mental health treatment with a broader vision of social justice and liberation, Fanon empowered patients to find their own paths to healing and self-realization within their cultural contexts. His ultimate goal was to help patients reclaim their sense of self-worth and identity, effectively decolonizing the practice of mental health care. However, Fanon seemed to feel that such kindnesses are not enough, or quick enough. He believed there needs to be a shock to the system, literally and figuratively, or people will go on thinking and behaving as they always have. In the literal sense, he used a lot of shock therapy, both the electroconvulsive and the insulin variety. While this seems to be at odds with his progressive approach, he viewed it not as a way to enforce conformity, but as a catalyst for breakthrough and transformation. Today, the use of shock therapy is on the wane because it seems so risky and invasive, while the use of psychedelics to break through entrenched patterns of thought or behavior is increasing. In both cases, the idea is to create a sort of disruption in the usual functioning of the mind, potentially allowing for new perspectives and healing to emerge. Both Fanon's approach and modern psychedelic therapy emphasize the importance of context, integration, and ongoing support. It's not just about the shock or the trip, but how it's understood and integrated into a person's life. Shock therapy and psychedelics may help to free individuals from patterns of thought that needlessly limit them, but how did Fanon propose changing society’s sick mind? Short of putting LSD in the drinking water, there’s no way to break everyone’s entrenched patterns of thought at once. That’s where armed rebellion comes in, including terrorism. Violence, to Fanon, is a kind of shock therapy. ViolenceFanon viewed violence as a potent means of breaking entrenched patterns of thought, particularly in the context of colonial oppression. He’s sometimes misquoted as an advocate for violence, but his point was more subtle. Fanon thought the violence of the colonized against their colonizers could serve as a kind of shock therapy for both parties. If the colonizers simply gave freedom to the colonized, that would do nothing to change their sense of inferiority. For the colonized, violence could be a way to break free from helplessness. For the colonizers, it could shatter their illusions of superiority. Violence has the power to reset the psychological dynamics between the oppressor and the oppressed. It's a dramatic way of asserting one's humanity and agency in a system that denies both. Fanon cautioned that violence alone isn't enough, just as electroshock or psychedelics are not enough. Shock therapy is the spark that can ignite change, but not the fuel that sustains it. It needs to be part of a broader process of education, community building, and cultural reclamation. The goal isn't just to overthrow the oppressors, but to create a new, more equitable society. Violence is a dangerous method of decolonization. You never know what will happen when you let loose the dogs of war. There’s got to be a better way than burning the whole thing down, killing millions, and leaving everyone traumatized in the process. The Beloved Community

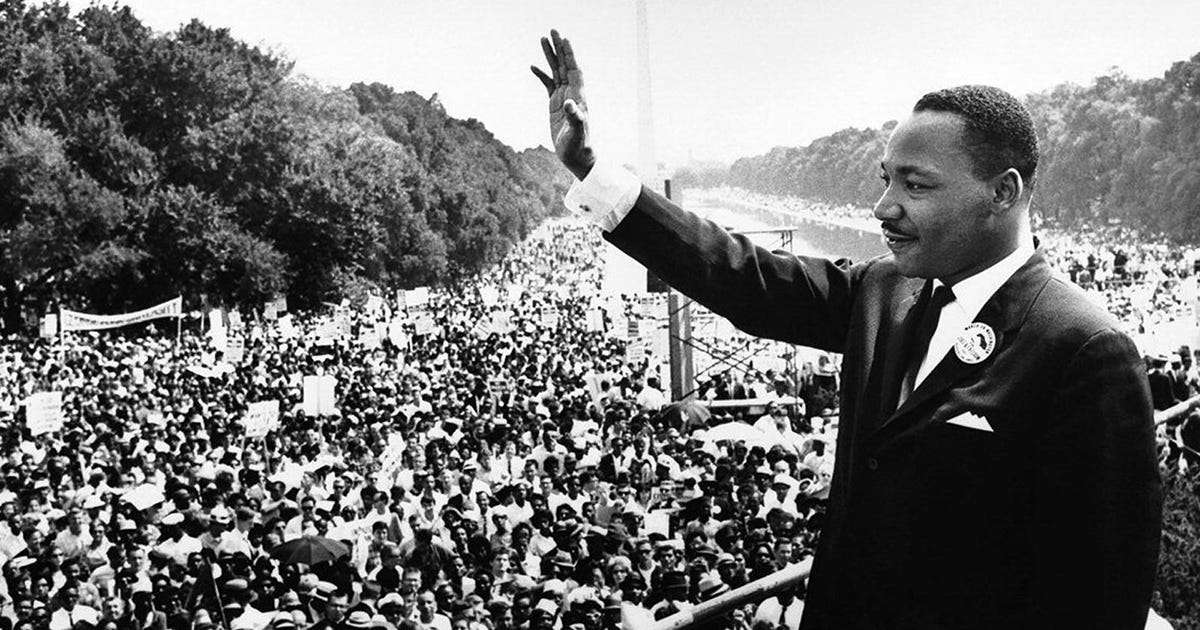

Martin Luther King had another way of overcoming colonization that was explicitly non-violent. He envisioned a global Beloved Community. In this ideal society, poverty, hunger, and homelessness would not be tolerated because international standards of human decency wouldn't allow it. Racism and all forms of discrimination, bigotry, and prejudice would be replaced by an all-inclusive spirit of sisterhood and brotherhood. In the Beloved Community, conflicts would still exist, but they would be resolved peacefully and without bitterness. King saw it as a realistic, achievable goal that could be attained through a critical mass of people committed to and trained in the philosophy and methods of nonviolence. The end goal of nonviolence, in his view, was not to defeat the colonizer but to win their friendship and understanding. In essence, the Beloved Community represents a state of heart and mind, a spirit of hope and goodwill that transcends all national and racial barriers. It's about creating a society where love and trust triumph over alienation, where peace with justice prevail over despair. If King’s concept sounds incredibly naive, perhaps you’ve bought into the colonial master’s lie, that violence, his violence, is justified to maintain a social order and nothing short of more violence will upend it. To my ears, it’s more reasonable to believe that we can win an opponent's friendship by offering peace and understanding than it is to expect that, if we enslave someone, they’ll be grateful for it. It’s no more crazy to believe that a spirit of hope and goodwill can transcend barriers than it is to believe economic growth can continue forever. If we’re going to believe a lie, can’t it be one that appeals to our better nature? Isn’t King’s vision something us Losers can belong to? Couldn’t it be something the Clueless could manage? If it was reinforced by governments, businesses, the media, and our education systems, wouldn’t we learn to believe it? Wouldn’t the proclamation of it by the Sociopaths win something no amount of gold can buy, the security of knowing that the colonized will not be coming for them with pitchforks, demanding retribution? ConclusionSo, what can we learn from colonization? Whether we're talking empires, corporations, or dysfunctional families, the same patterns of control and alienation keep coming up. Fanon and King offer us different roadmaps for breaking free; one through shock therapy, the other through building a Beloved Community. Both challenge us to examine how we might be playing into these systems without realizing it. Decolonizing our minds isn't a simple matter; it's an ongoing process of creating new, truly liberating structures. The goal? A world where no one's stuck wearing a mask that doesn't fit, where we value connection over control. It beats being a cog in someone else's machine. Let's insist on a world where everyone is free and treated fairly. If You Want to Read MoreBooks that have influenced my ideas about colonialism are Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks, and The Wretched of the Earth; as well as, The Rebel's Clinic:The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon by Adam Shatz and Decolonizing Psychoanalytic Technique: Putting Freud on Fanon's Couch by Daniel José Gaztambide. Along the same lines, Gaztambide also wrote A People’s History of Psychoanalysis: From Freud to Liberation Psychology. Concerning maroon societies, there’s, Maroon Societies : Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas by Price, Richard; Slavery's Exiles: The Story of the American Maroons by Sylviane A. Diouf; and Flight To Freedom African Runaways and Maroons in The Americas by Alvin O. Thompson. Venkatesh Rao does not explicitly mention or focus on colonialism in his book, The Gervais Principle. The colonial analogy is my extension of Rao's ideas. But there are other books that do: Bullshit Jobs: A Theory by David Graeber and The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power by Joel Bakan. For more about growth, see, The Growth Delusion: Wealth, Poverty, and the Well-Being of Nations by David Pilling and Prosperity without Growth by Tim Jackson. The identification of colonialism within the family is also my own, but this book makes a similar point, The Narcissistic Family: Diagnosis and Treatment by Stephanie Donaldson-Pressman and Robert M. Pressman. For a comprehensive understanding of Martin Luther King Jr.'s concept of the Beloved Community, a highly regarded source is The Beloved Community: How Faith Shapes Social Justice from the Civil Rights Movement to Today by Charles Marsh. Then, there’s Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? by Martin Luther King Jr., himself. You're currently a free subscriber to The Reflective Eclectic. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Monday, 2 September 2024

Decolonize Your Mind

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Making Sense of the Voices in Your Head

With Internal Family Systems ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

https://advanceinstitute.com.au/2024/04/24/sunnycare-aged-care-week-10/?page_id=...

-

barbaraturneywielandpoetess posted: " life on a rooftop can be short ; depends whether one looks down or up . ...

No comments:

Post a Comment